South East Wales Regional Transport Plan – DCFW Consultation Response – May 2025

Category: Comment

The Design Commission for Wales is undertaking a second engagement on the new draft guidance – Designing for Renewable Energy in Wales. The consultation opened on 24 April 2023, and the deadline to respond is 19 June 2023.

Please see our letter for more information.

To comment, please complete the questionnaire as per the format indicated in the consultation materials and send it by e-mail to connect@dcfw.org.

Thank you.

One of the six elements of the Placemaking Wales charter is ‘Identity’. A vibrant language and cultural richness are also cornerstones of the Well-being of Future Generations Act. Many Welsh place names, whether ancient or modern, are readily perceived by their meaning, and their meanings can still be understood in modern Welsh. But how do they signal ‘identity’ and could a place’s identity be affected by a changing climate?

Welsh-language place names often tell us about the landscape of the place, as well as its location, history, and heritage. Name is an integral part of its identity. With the effects of climate change threatening to shape the future of the Welsh landscape, it is more important than ever that we cherish the meaning of these names. When the climate changes, the landscape changes – land that has been shaped, known, and understood for generations. As such, without significant action, our place names could become like headstones, inscriptions only of what once was.

Aberteifi, Abergwyngregyn, Aberystwyth, Aberarth, Abertawe, Aberdaugleddau, are located near the coast, with ‘Aber’ often meaning the confluence of two bodies of water. A changing landscape brought about by climate change would mean that these names are no longer descriptive.

Places with names such as Glanyfferi, Glanyrafon, Glan-y-wern, and Glan-y-gors, with ‘Glan’ often indicating a location near a body of water, could have their landscapes altered and shaped by the changing tides and flooding. Traeth is another word that appears in Welsh place names, meaning ‘beach’. Pentraeth, Traeth Mawr, Trefdraeth and Traeth Bach all feature this element.

Cors Fochno, Cors Caron, Cors Ddyga, and Glan y gors all feature the word ‘cors’, which refers to a bogland. With industrial peat excavation as well as burning affecting bogland, it is of key importance that these landscapes are protected, recognised for their importance, and celebrated. ‘Gwern’ refers to the alder-tree, which grows on damp land and in bogland, and features in names such as Gwernydomen, Gwernymynydd, Glanywern, and Penywern.

Landscape and language are filled with clues that can tell us about the history of an area, and the history of people and communities across Wales. ‘Ynys’ means land surrounded by water, and features in island names such as Ynys Llanddwyn, but also in mainland areas, such as Ynyslas near Aberystwyth.

Morfa refers to saltmarsh or moorland, and features in place names such as Tremorfa, Morfa Nefyn, Morfa Bach, Penmorfa, and Morfa Harlech. These landscapes could be greatly changed due to the use of pesticides and fertilizers on surrounding farmland, sea level rise, and pollution in rivers. If these places are transformed, can they still be marshlands?

Many elements of Welsh place names tell us about their landscape and location, such as Mign, Tywyn, Trwyn, Pwll, Rhyd, Penrhyn, Sarn, Ystum, Cildraeth, Gwastad, Isel and Gwaelod – these are often commonly understood even among those who do not speak Welsh fluently. They are meaningful – they bind those of us who identify as Welsh in a shared culture.

It is imperative that these place names are acknowledged and celebrated. Places and place names don’t exist in a vacuum: they are the product of action and interpretation. Whether they are recent or ancient, someone’s way of life has shaped that place, and someone looked at the landscape and decided to name it according to their understanding of it. That shaping and those names transform land into place.

The Welsh landscape is still rich with these names. Seek them out, discover their meaning, connect with the past that shaped them – and the land will speak.

by Efa Lois

Our colleague Professor Juliet Davis shares her thoughts today to mark International Women’s Day and help #breakthebias #IWD #IWD2022

Professor Juliet Davis

Years ago, I was lucky to be able to go on a site visit to a well-known public building in London when it was still a construction site. The first thing I had to do at the start of the visit was pick up a hard hat and suitable footwear at the contractor’s office. One of the foremen was tasked with handing out boots of suitable size to the visitors. When he came along to me, he worried that he didn’t have boots small enough. I stood before him, the top of his head level with the bridge of my nose. “What size do you take?”, he asked, nicely enough. “Size 10, EU 45”, I said. I’m more than six feet tall; it’s not surprising.

This capacity to hold in place a stereotypic image even when confronted with evidence that clearly defies it is a kind of bias. This, of course, is just an amusing story, but it illustrates a serious and often forgotten fact – that what the eye apparently sees is not necessarily what is, and that perception of another is always developed in a social context. As John Berger argues, different ‘ways of seeing’ are possible. Social and physiological factors meld together to form durable images, preconceptions, and expectations of other people.

Seeing and visualising people and places are core activities of architects and, hence of architectural education. Designers learn early on to observe people’s interactions and uses of everyday spaces, and to situate people within the places they imagine. Do we teach them enough about who they see and how, about how preconceptions might shape their analyses? About how the frame of a picture can include and exclude? About the assumptions regarding people, roles and potentials that architectural plans and renderings can contain?

To commit to addressing bias in an architecture school is to recognise a multifaceted project, an opportunity encompassing new approaches to design history, reworkings of old pedagogical forms such as the ‘crit’ and the transformation of studio cultures leading to long working hours. But, for me, tackling seeing and perceptions is also vital if the young architects of today are not to perpetuate injustices rooted in bias, through tomorrow’s built environment, limiting the opportunities of girls and women at different stages of life and from different cultural backgrounds, to navigate public spaces comfortably and safely, and to develop and realise their potential in the work place.

As my opening story suggests, tackling issues of seeing is an urgent task across the building industry given the potential for stereotypes to affect far more than a choice of boots, casting doubt over women’s professional knowledge and competence, and shaping their capabilities for fulfilment in practice. Schools have a role to play in this too as they prepare women for careers in design practice and engage with professional bodies. As the first woman head of the Welsh School of Architecture, I am committed to all facets of the project.

Professor Juliet Davis is the Head of the Welsh School of Architecture.

Our colleague Cora Kwiatkowski shares her thoughts today to mark International Women’s Day and help #breakthebias #IWD #IWD2022

Cora Kwiatkowski

The construction industry is without doubt high-pressured with a lot at stake – programme, budget – and ultimately the success of places and spaces that we create for people for years to come. Projects become more and more complex with bigger teams involved. We therefore need to make a lot of decisions quickly – and this is where our brains have a natural tendency to simplify information which not only applies to our work but the people we work with. Many behaviours and attitudes arise from, are influenced by and depend on mental shortcuts and categorising people into stereotypes without even realising it.

Bias is everywhere: gender, age, origin, accent – even height and beauty. We all need to keep an open mind and check ourselves to step back from preconceptions, even if it takes more effort.

Although it is now more widely acknowledged and better understood, our industry still has a long way to go when it comes to bias. Perceptions are very hard to shift. Recognising achievements and respecting everyone for their contribution and personality in this mostly white middle-aged male dominated industry will help to change the status quo – it should become normal to see women and people of colour in strategic roles, leading companies as well as high-profile projects, bringing the industry forward as a whole. And when we meet them, let’s lift them up together and make them even more visible.

Looking at my own work, I couldn’t have succeeded alone in any of the amazing projects I designed, it needed the support of a whole team to make it all happen based on mutual respect, seeing the ‘real person’ rather than the stereotype, communication and teamwork – valuing everyone’s contribution. Creating long-term relationships and a network of support not only makes projects more fun but enables honest conversations so potential obstacles can be overcome more easily. It feels definitely easier to do that in a multi-facetted environment such as higher education where there is already more diversity among designers, clients and end users alike.

Single perspectives don’t give rise to innovation. One person doesn’t have all the answers. Not all of us think the same way. Different perspectives and ideas accelerate creative problem solving. Let’s not be lazy and narrow in our thoughts but open and inclusive so that we all benefit!

Cora Kwiatkowski is a Divisional Director at Stride Treglown and a DCFW Commissioner.

Our colleague Chithra Marsh shares her thoughts today to mark International Women’s Day and help #breakthebias #IWD #IWD2022

Chithra Marsh

A THANK YOU LETTER TO A STRONG-WILLED MUM

Hi Mum,

It’s been a long time!

I’ve been thinking about you a lot lately – about the lessons you taught me through your many stories, repeated over and over again, and how you guided me to be a strong Indian woman with ambition.

I loved learning that you were the first working woman in our family. Bucking tradition must have been difficult, but you were rewarded with a job at a telephone exchange which helped you to hone your skills in English and make close friends. Sounds like you had lots of fun too!

Taking another courageous step, you left the safety of your family home in Bangalore and moved to the UK with Dad in the 1960s, losing no time in looking for a job and forging your independence. You refused that job in a sari shop, offered to you at the job centre as the only option for an Indian woman, and started a long career in Accounts.

You wanted to fit in, so you did what you had to do in order to be accepted in this new world. You dressed in ‘Western’ clothing, saving your saris for special occasions. You were careful with your cooking, too, making sure it didn’t smell too strong so as not to upset the neighbours. I wish you had been accepted and valued just as you were – a proud Indian woman with ambition (who cooked amazing South Indian food!)

You wanted the same for me right from the start, firmly telling my first teacher to treat me the same as all the other kids so that I didn’t feel different. You encouraged me to respect my Hindu heritage and culture, and held high expectations for me when it came to my education and career prospects.

At times, I didn’t appreciate what you were trying to do, but with hindsight, I know you were trying to give me better opportunities to be accepted and thrive. Now that you are no longer here, I have your voice in my head and your stories for inspiration.

Thanks to you, I am committed to advocating for inclusivity and diversity in the building industry. I want to bring about positive change so that no one else feels the need to change who they are in order to fit in.

No bias. No stereotypes. No discrimination.

Thank you, Mum.

#breakthebias #IWD2022

Chithra Marsh is an Associate Director at Buttress Architects.

Our Chief-Executive Carole-Anne Davies shares her thoughts today to mark International Women’s Day and help #breakthebias #IWD #IWD2022

Carole-Anne Davies

The one.

The one who…

…checks herself before entering the room.

…can’t believe she’s there.

…stands out and not in a good way – she thinks.

…whose skin is different from the others.

The redhead.

The big one.

The stroppy one.

The chopsy one.

The one who apologises whenever she speaks…sorry can I just…

The one who isn’t academic.

The one who is academic.

The one with ‘the hair’.

The gay one.

The trans one.

The old one.

The junior one.

The reader.

The one who didn’t catch where the others were going.

The one who isn’t just ‘the one’ but is only one, among millions, getting the message every day that they don’t fit.

How exacting the dimensions are in a biased world.

#breakthebias #IWD2022

Carole-Anne Davies is the Chief Executive of the Design Commission for Wales.

To celebrate World Book Day 2022, we asked DCFW friends and colleagues for their book recommendations.

Cora Kwiatkowski

I always loved books. I generally read whatever falls into my hands and is recommended to me, and there is not enough space on my bookshelves to hold them all so some had to be banned to the loft, only to be pulled out again after a while, and some read again. As a teenager, my favourite place to read books on holiday was sitting about 5 meters up in a tree!

I do own a good selection of architecture and design books although more recently they have been replaced by newsletter and internet articles.

Nevertheless, sometimes there are books that catch my eye, and I just have to buy them, despite the lack of space. After visiting the Renzo Piano exhibition at the Royal Academy in London in September 2018 – January 2019, I was so inspired by the short film and interview by Thoms Riedelsheimer that was shown in the room where ‘Piano Island’ was built – a large model with all the project he has been working on – that I wanted to relive the experience and continue to be inspired by Piano’s ideas. ‘Renzo Piano: The Art of Making Buildings’ interpretive text centrepiece is a similar interview and it felt like Renzo Piano being in the room.

His work has followed me in my whole career. When I was a student, I was deeply impressed by the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre, Nouméa (1998), which comprises of elegant structures which combine tradition and context with modern engineering and cultural appeal. Now I see The Shard (2012), one of his more recent buildings, most times I am in London, a needle-sharp marker of the centre.

Piano talks about ‘beauty’ – a well-discussed word recently – and how incredibly complex it is. Something we all aspire to; it is being described like Atlantis. Something you look for but that you’ll never find- but you can come close. Our job as architects is about creating places for people and bringing the beauty to the world we live in.

Taking a step back from the daily design work and all its challenges, it is lovely to be reminded about the importance of our jobs and the impact our buildings can have.

I’m currently reading ‘Spring Cannot Be Cancelled’ – David Hockney in Normandy’. A reminder of the power of art for distraction and inspiration. This life-affirming correspondence between two old friends – Hockney and Martin Gayford – not only lets us take part in their life but is also very personal – David Hockney’s simple way of life in the middle of lockdown, getting closer to nature again and enjoying being undistracted. Be prepared for more book recommendations and enjoy beautiful drawings, some previously unpublished. David Hockney shows us how to see things and how his life has changed, concentrating on the essential things in life. Highly recommended!

Cora Kwiatkowski is a Divisional Director at Stride Treglown and a DCFW Commissioner.

Links:

Read and watch the text and films from the Renzo Piano exhibition film here. This 17-minute, dual-screen film installation was commissioned especially for the exhibition. © Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2018. A film by Thomas Riedelsheimer.

Buy the books:

Renzo Piano: The Art of Making Buildings

Spring Cannot be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy

Jon James

Books and the variety of reading inspires us all in many ways – I have always tried to mix architectural essays with books that can give a me an alternative cultural view that I will never experience myself. I have a bit of a bad habit of having a few books on the go at the same time and tend to stop and restart: sometimes months apart!

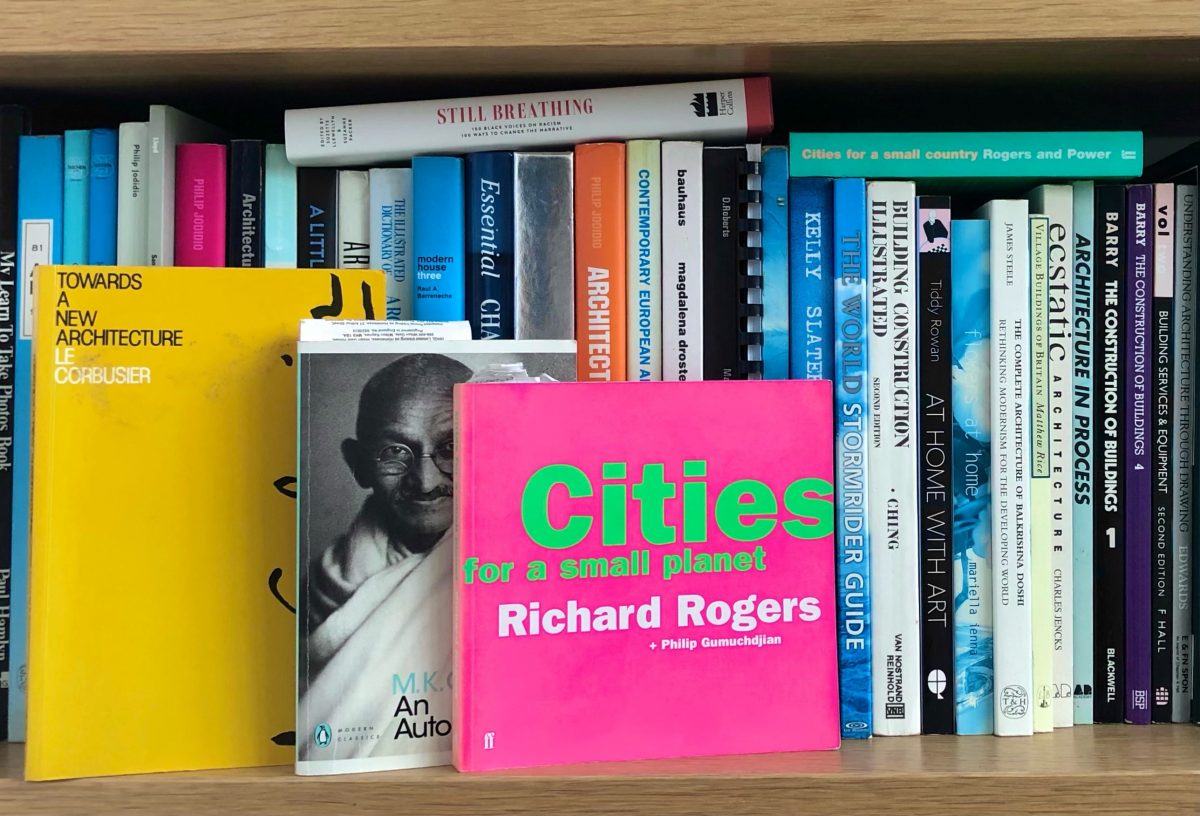

I currently have two books on the go Gandhi’s autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth and I have also just started Still Breathing: Black Voices on Racism – 100 Ways to change the narrative. Both are about first-hand experiences and insights that simply make you sit up and think in so many ways about the reality and bravery of facing adversity. Almost everything I read is non-fiction, biographical/ autobiographical, however in contrast to this I recently read a book, highlighted for its reaching ideas called The Power by Naomi Alderman. The story in its simplest terms is about women gaining powers to become the dominant gender in the world. It is brilliantly written, thought provoking and gripping from start to finish.

In relation to Architecture, there are a number of books that stand out for me. Most are classic reading for an Architect but none the less important and have inspired me throughout my career. Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture is important for its arguments in generating discussion at various levels. It ranges from the human modular scale to the city wide urban planning. It reminds me to think wider in context and learn from the past, it encouraged me to travel as much as I can and understand historic places such as the Acropolis. This in turn informs the future, but we must also be in the present and not simply recreate the nostalgia of the past. This seems particularly poignant to me as we urgently face the climate emergency; and that leads me to Richard Rogers’ brilliant Cities for a small planet (and the complementary Cities for a small country), written some 25 years ago it rings true on many fronts today. Most significantly is how culturally a shift is needed to change what we perceive as value in our built environment which has been dominated for decades by real estate making money. I like to think this is now changing and that the emphasis is now on sustainability.

Aside from the written text, being in a visual profession, I enjoy books without words as well. Some books feature design ideas/ buildings/ details and materials of how our buildings and spaces are made and what they are made of.

Finally, as an amateur cyclist and living in South Wales I have enjoyed my signed autobiographical accounts by Geraint Thomas, Tour De France Winner. In particular his adventures, over and around the hills, Valleys and Mountains of South Wales. Anyone who has cycled them can relate to his experiences, even if it is at a slightly different pace!

World Book Day is a great excuse to stop, reflect and share. I am looking forward to reading other people’s recommendations so I can continue to find new inspiration.

Jon James is a registered Architect, a certified Passive House designer, and a DCFW Commissioner.

Buy the books:

Still Breathing: 100 Black Voices on Racism–100 Ways to Change the Narrative

Towards a New Architecture – Le Corbusier

Cities for a Small Planet – Lord Richard Rogers

Cities for a Small Country – Lord Richard Rogers

The Tour According to G: My Journey to the Yellow Jersey – Geraint Thomas

World of Cycling According to G – Geraint Thomas

Mountains According to G – Geraint Thomas

Gayna Jones

Invisible Women – Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men by Caroline Criado Perez opened my eyes to ‘how in a world largely built for and by men, we are systematically ignoring half the population’. I am a woman in a world designed by men!

My journey to the Design Commission began in social housing, where design can be poor. Reading this book, my experience began to make sense.

In my kitchen, some cupboards are high. Most men could reach, but as a 5’4” woman, I can’t. Criado-Perez points out ‘seeing men as the human default is fundamental to the structure of human society’ and she provides lots of data to prove it. A simple example is the way things as diverse as a piano and a smartphone are designed for the average size of a male hand.

She demonstrates that cars are designed for and by men, creating real safety issues for women. A frustrating example for me is car seat belts; I have never found a comfortable one!

Housing estates are largely designed for the needs of cars rather than people often ignoring the needs of children in particular. Partly due to the pandemic we are moving away from valuing cars over pedestrians, but most estates are still designed around highways, car parking and car use. The transport profession is highly male dominated. Criado-Perez says, ‘the available research makes bias toward typically male modes of transport clear’. Transport is designed largely around male travel patterns – by default; two daily journeys to and from work, rather than multiple trips to school, shops, relatives, healthcare. It caters for men travelling on their own, rather than women who travel with shopping, buggies, children, or elderly relatives. ‘Rough, narrow and cracked pavements littered with ill placed street furniture combined with narrow and steep steps makes travelling around a city with a buggy extremely difficult’. Many women feel unsafe in public places like bus stops, yet urban places are designed taking no account of this. Street lighting is given little or low priority.

Another good example, is from Sweden, where they prioritised clearing snow from roads for cars, rather than from the pavements which are mostly used by women pedestrians. Changing this priority dramatically decreased accidents.

This book helps you see why things are as they are & how a change in focus is long overdue. I highly recommend it.

Gayna Jones is the Chair of the Design Commission for Wales.

Buy the Book:

Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men – Caroline Criado-Perez

Martin Knight

I love being surrounded by books, even though I often cannot imagine when I will find time to read them. January brings a rare opportunity, with long nights and a logjam of birthday and Christmas books to work through.

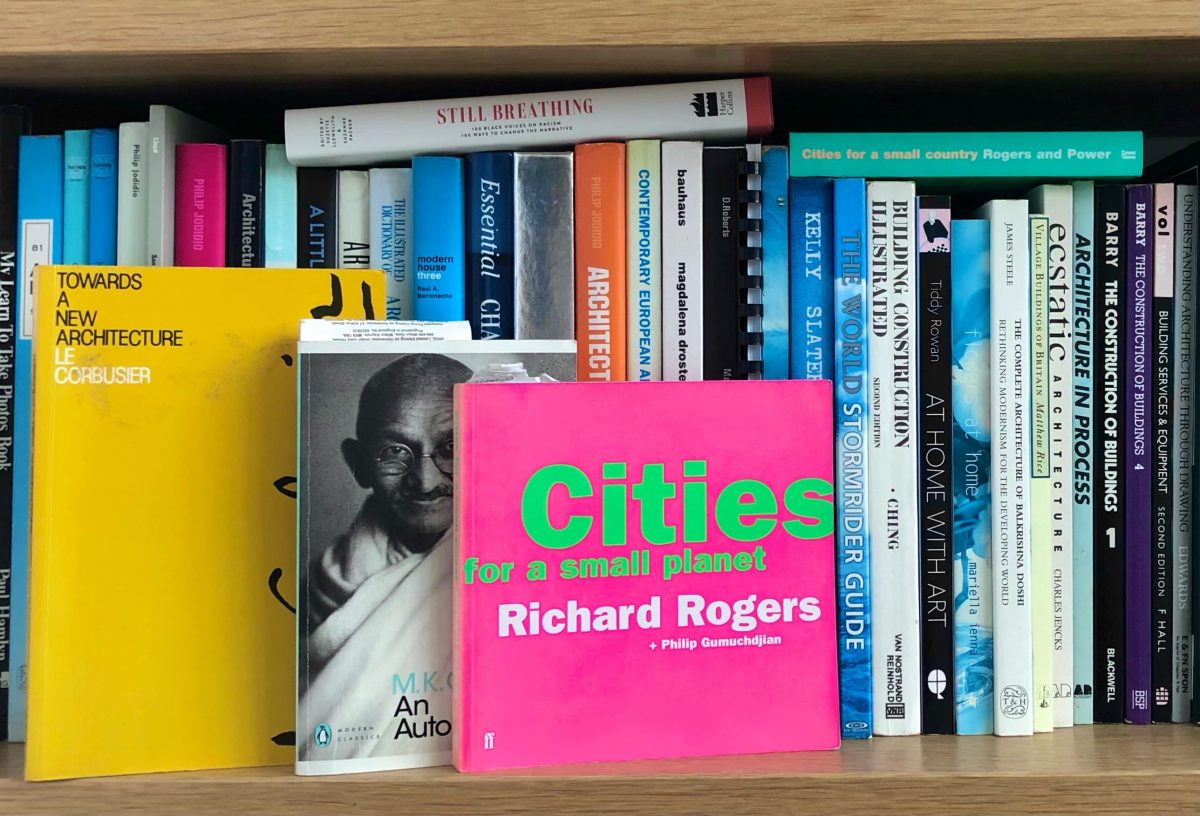

I have selected four books to celebrate World Book Day, three of which are current and encompass reading for pleasure as well as knowledge. The fourth I have read many times and is a source of inspiration and enlightenment as well as enjoyment.

I recently bought David Mellor: Master Metalworker while visiting the David Mellor Cutlery Factory in Hathersage, Derbyshire. Although aware of their handmade cutlery and beautiful factory in the Peak District, designed by Hopkins Architects, I knew less about the role of David Mellor in post-war British design. His work includes exquisite tableware for society events and street furniture that is immediately familiar, including the iconic British traffic lights, pedestrian crossing (with the inviting button that every child has pressed), and bus shelters. The importance of design, whether for extraordinary events or everyday life, is lovingly chronicled.

The daily trials of last year’s Tour de France are told first-hand with brutal honesty in Tour de Force, by Mark Cavendish. The fast-paced narrative is even more powerful given his return from several years of illness, injury and poor form. It is gripping to read the painstaking preparation of athlete and machinery – always under the scrutiny of a sport with a dirty history – combined with the supreme self-belief of an elite athlete.

My uncle loaned me his copy of Island Years, Island Farm by Frank Fraser Darling last summer (I have since bought my own!), following a conversation about our own island heritage. Another account of an arduous pursuit – measured in seasons rather than in split-seconds – this chronicles one family’s true adventures on various tiny Scottish islands in the 1930s, observing wildlife and learning to farm. It describes a slow, rewarding and respectful relationship with nature that modern life has largely forgotten to its cost.

The final choice is my favourite book. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert M. Pirsig is a story of a motorcycle road trip, of a father and a son, of philosophy and reality. The road trip is a metaphor for life and the storyteller explores themes including Quality and a Sense of Place, which resonate with my passion for bridge design.

Martin Knight is Founder and Managing Director of Knight Architects, and a member of the DCFW Design Review Panel.

Buy the books:

David Mellor: Master Metalworker

Tour de Force – Mark Cavendish

Island Years, Island Farm – Frank Fraser Darling

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance – Robert M. Pirsig

Joanna Rees

Wet 1980’s Saturday afternoons in Pyle Library. The smell of plastic lining and rustle of shushing. Books bought in Smiths in the Rhiw Centre and read in the car before we got home. The excitement of a birthday book token for Lear’s and a trip to Cardiff. It’s been a lifelong love of books, storytelling and the escapism they offer. I can’t pretend that reading was a great influence on my career; if my early years were anything to go by I would have been running a boarding school or doing pony jobs with Jill.

Now, I love books with a sense of place, history and architecture where I can step into another’s thoughts and landscape. From the opium wars of a Sea of Poppies (Amitav Ghosh), to war torn Penang and divided loyalties of The Gift of Rain (Tan Twan Eng) I like being transported back in time and made to think. It’s the books that stay with you, wondering whether the Sealwoman’s Gift (Sally Magnusson) based on a pirate raid of Iceland in 1627, and the family taken in slavery to Algiers, were better off eating pomegranates by the fountains or stuffed puffins on the windy cliffs.

Nature writing too, Robert Macfarlane’s glorious writing of the British landscape on land, language and the Underland. James Rebanks’ Shepherd’s Life with his Hardwick Sheep and the challenges of restoring traditional farming in the Lake District. Not to forget the delight of a small anthology of poetry. John Clare’s feeling for nature, Robert Frost’s two road diverging in that wood and Hardy’s Darkling Thrush. And that Boathouse in Laugharne offering up, ” the mussel pooled and the heron Priested shore”

Finally, for insomnia, always poetry and always Mary Oliver for hope and Wendy Cope for that wistful sardonic twist.

Joanna Rees is a Partner at Blake Morgan, and a DCFW Commissioner.

Buy the books:

Sea of Poppies – Amitav Ghosh

The Gift of Rain – Tan Twan Eng

The Sealwoman’s Gift – Sally Magnusson

The Shepherd’s Life – James Rebanks

Faber Nature Poets: John Clare

The Collected Poems – Robert Frost

New and Selected Poems – Mary Oliver

Links:

Read ‘The Darkling Thrush’ by Thomas Hardy online.

Read ‘A Poem in October’ by Dylan Thomas online.

An article on John Clare’s poetry.

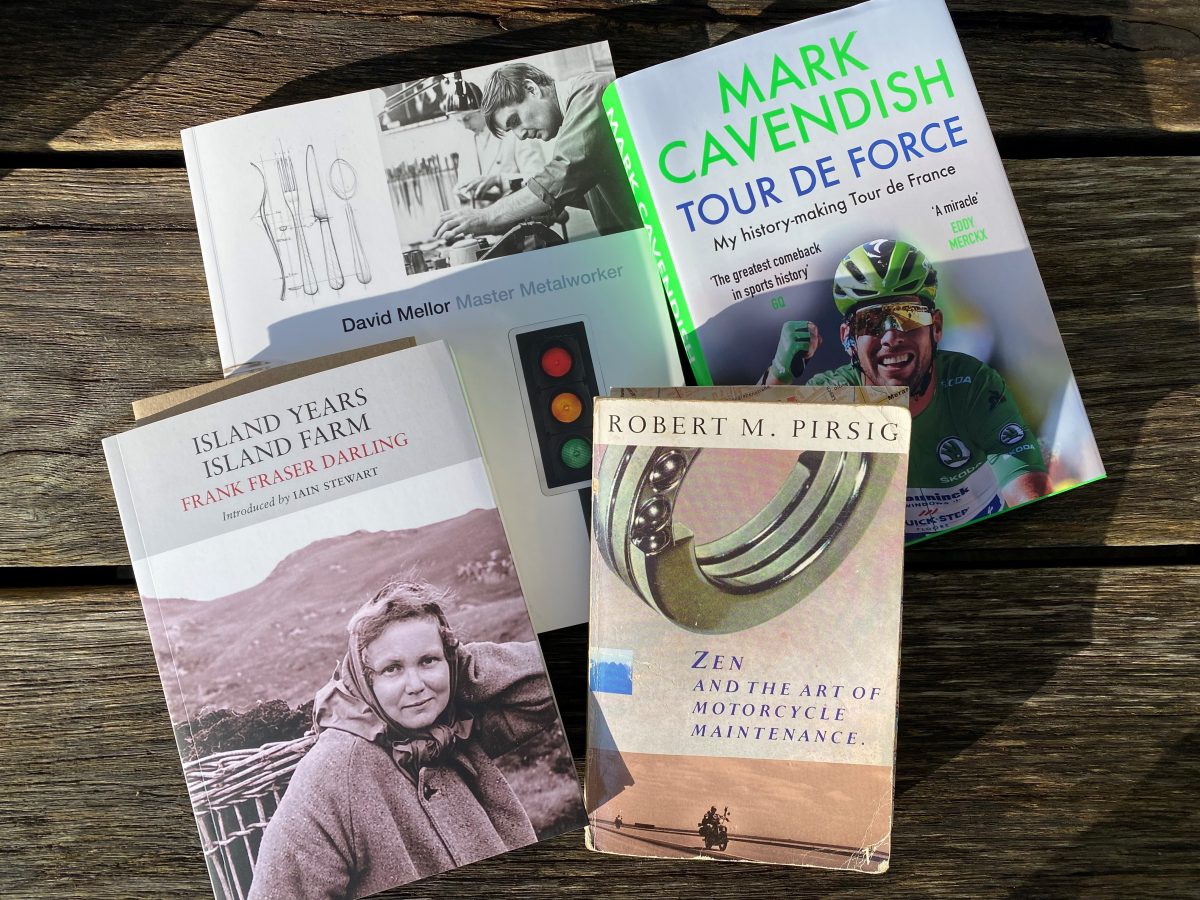

Fiona Nixon

There seems to be a common thread to all my favourite fiction books, and that is, a strong sense of place, or a building that is central to the plot. I love a well-researched book and one set in a real place. Is it just me that checks out the locations out on Google Earth?

My all-time favourite, and one I frequently recommend is Oscar and Lucinda by Peter Carey. There are just so many fascinating elements to Carey’s masterful storytelling; the excruciatingly awkward Oscar, the unconventional Lucinda and her trials working in a man’s world in the late 1800s, scandalously drawn together by their gambling addictions. The detailed and humorous narrative shifts seamlessly between the different characters’ perceptions of the events that unfold. I love the facts and metaphors around glass, particularly the Prince Rupert’s drop – a ‘firework’ in the world of glass manufacturing. The story is drawn from miscommunications and misunderstandings and culminates in the transportation of a glass church over unchartered land and down the Bellinger River.

The Bone People by Keri Hulme is a more challenging read. Set in New Zealand with Maori influences, it is an unconventional story of love and relationships between a woman, a man and a child, but with themes of isolation, fear and violence. Kerewin lives in a stone tower, which she deconstructs and rebuilds in a different way, symbolising the changes in her life.

In the last year I’ve read two more excellent books with houses at their cores, both coincidentally set in the outskirts of Philadelphia. The Dutch House by Ann Patchett, centres on a family’s attachment to a large eccentrically designed suburban house – More glass, more misunderstandings and more bad decisions. Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver follows two families living in the same house at different times, 1870 and 2016, each struggling to maintain the house and keep their families together. It has more contemporary themes of capitalism, poverty, feminism and mental health.

What am I reading now? Well a slight shift from buildings, and not fiction, but definitely deeply rooted in place – English Pastoral by James Rebanks. ‘A story of how, guided by the past, one farmer began to salvage a tiny corner of England that was now his, doing his best to restore the life that had vanished and to leave a legacy for the future.’ I’m only two chapters in, but I think I’m going to enjoy it.

Fiona Nixon is an Architect, a DCFW Commissioner, and a former Head of Estates Projects at Swansea University.

Buy the books:

Oscar and Lucinda – Peter Carey

The Dutch House – Ann Patchett

Unsheltered – Barbara Kingsolver

English Pastoral – James Rebanks

Jamie Brewster

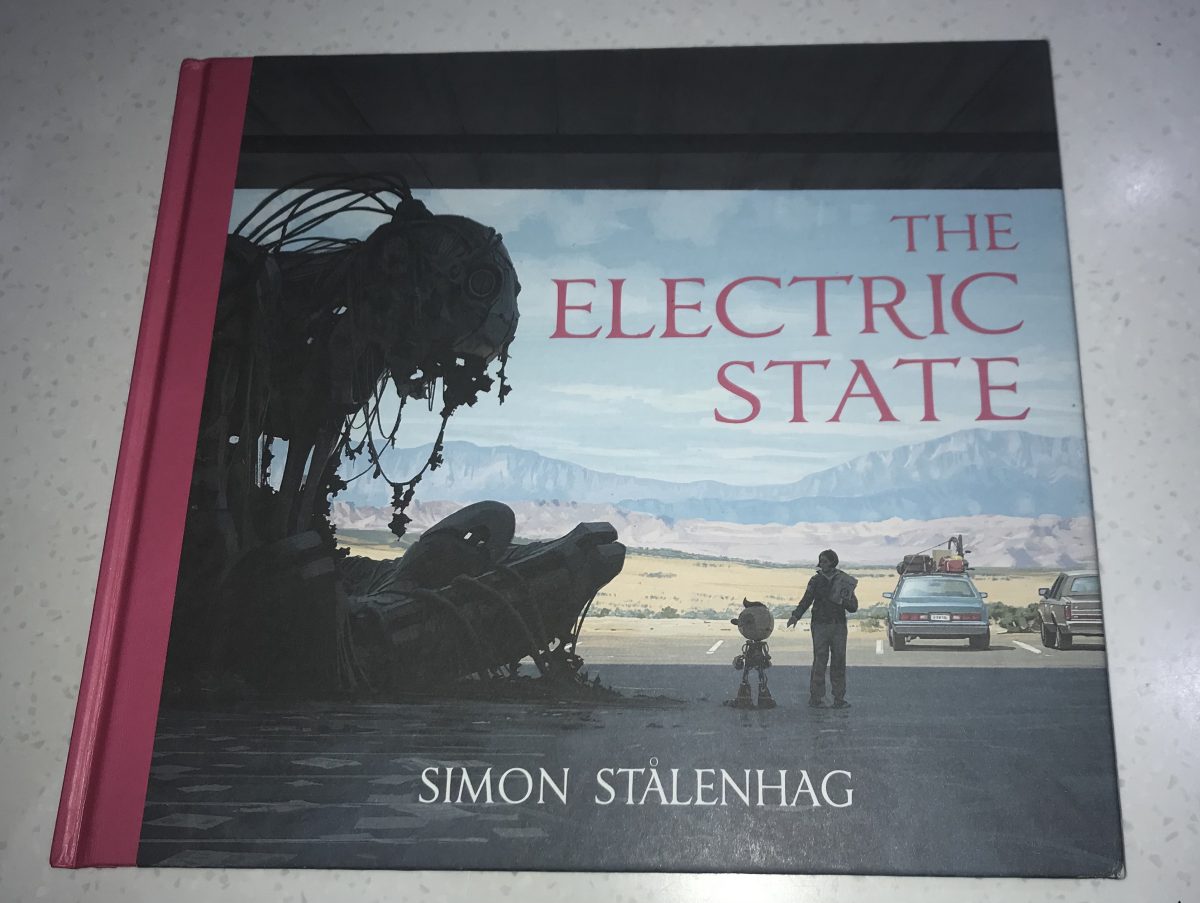

The Electric State – Simon Stålenhag

I first discovered the work of Simon Stålenhag six years ago. Whilst searching the web for imagery I came across his arresting images which at first glance seemed convincingly real. Almost photo-realistic in execution, it was only the subject matter, the strange juxtaposition of rural landscape with other-worldly infrastructure and technology that suggested otherwise. I delved deeper and encountered an extensive portfolio of beautiful paintings, all sharing that unsettling quality in combining the everyday with the unusual. With clear influences of Syd Mead, Ralph McQuarrie and Edward Hopper, the appeal was even greater in realising that what were assumed to be paintings in oil/acrylics were in fact 100% digital. On his website, he frequently shares magnified extracts of his ‘paintings’, generously explaining his technique. I have spent hours ‘reading’ his imagery, marveling at the supreme skill in digital image-making.

And yet he is also a skilled writer. The images are created to support fascinating stories which reminisce on alternative histories. Firmly steeped in sci-fi, his is a reverse-engineered vision of the future viewed through a nostalgic lens. Having concentrated his story telling on his native Sweden in his first two books, The Electric State takes place in a reimagined version of American history.

A road trip with a difference: the story traces the journey of Michelle and her small robot companion Skip, from east to west coast. On the trip through what appears to be classic American landscape, they encounter strange yet beautiful structures, machines and a population in the grip of a techno-induced self -destruction. As the story progresses the mood and atmosphere of growing dread and darkness increases. The closing reveal of who/what Skip is adds a moving finale.

I’ve enjoyed this book many times using a different approach each time. Sometimes, I restrict my view to the images alone. Sometimes I do the reverse, focusing exclusively on the text. The experience is richly satisfying regardless how you choose to read the work. Either way, there is room for an ongoing interpretation whether using the visuals, the text or both as the source.

The common thread in Stålenhag‘s work, exemplified in The Electric State, is the idea of place. His ability to conjure real depictions of place by capturing mood and atmosphere through words and imagery makes this book hugely compelling and inspirational on so many levels.

Jamie Brewster is a Senior Associate Architect with DB3 architecture, and is a member of the Design Commission for Wales Design Review Panel.

Buy the book:

The Electric State – Simon Stålenhag

Steve Smith

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning – Laurie Lee

Moments of great change in a life are frequently marked by ceremony and public celebration. The change of leaving home for the first time is not one of these events. It is a marked by a powerful mix of parental sadness and pride, youthful anticipation and fear. The drama of the moment is concealed beneath commonplace salutations of farewell, and advice given sincerely but half in jest. The occasion is too personal, but also too momentous, to allow public ritual and ceremony to intrude on this private moment.

Leaving home is captured perfectly by the title and in the first pages of Laurie Lee’s book describing how he walked out from his childhood home to explore the world in 1934. Somehow he evokes the emotions of his mother without the use of a single word on the topic. Instead, there is a simple description of her waving farewell as he heads away carrying his violin to embark on this adventure and the next chapter of his life.

The tale that unfolds describes the encounters of this innocent and naive youth on the roads in Spain in the years before the cataclysm of WWII. He seems to travel safely through a simpler word, sure of his invincibility- a privileged state of mind given only to wandering, innocent youth. Gradually his innocence is tempered by growing evidence of impeding civil war in Spain.

Any reader who encounters the first chapter of this book will be enriched by it. If they go on to read further they will discover an adventure that will live on in their enriched imagination.

Steve Smith is an architect, Founder and Director at Urban Narrative. He is also a member of the DCFW Design Review Panel and an advisor to the Design Commission for Wales.

Buy the book:

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning – Laurie Lee

95cm Perspective

We were all 95 cm tall once, typically when we were about three years old. Do you remember what places were like from down there?

It can be easy to forget the perspective of a child from our lofty 5’ to 6’ height, or from the driver’s seat of a car. But children see and experience things differently – the joys, the dangers, the magic of places.

Being a parent or caregiver to a child also changes the perception of a place. Walking times multiply when you have little legs to account for, access to toilet facilities becomes all the more important with nappies to change or in the midst of potty training, and ‘stay on the pavement’ becomes a highway safety mantra but only works if there is a clearly defined pavement and there aren’t cars on it. Navigating and enjoying the city changes in the presence of children but their perspective is often overlooked in the planning and design of our town and city centres.

It is from this perspective that Urban 95 Academy want city makers to view the city. The Bernard van Leer Foundation and the London School of Economics and Political Science had developed a ‘leadership programme designed for municipal leaders across the world to learn and develop strategies to make cities better for babies, toddlers and their caregivers’[1]. The programme offers a fantastic opportunity for city makers to learn from international experience and draw upon it as they devise strategies for their own city. More information can be found on the Urban 95 Academy website.

As highlighted by Play Wales, all children have the right to play, a right in fact enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child[2]. Article 31 of the Convention says:

Every child has the right to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.

This includes not just young children but also older children and teenagers who often get actively designed out of spaces rather than being welcomed and accommodated. It is in this context that the charity Make Space for Girls was established to ‘campaign for parks and public spaces to be designed for girls and young women, not just boys and young men’[3]. Their research found that in many cases not only were teenage girls not well catered for in the design of public spaces, but they could also feel actively excluded by the design. They highlight the need to understand the context of any particular public space and to speak to girls in the area to develop creative solutions as there is no ‘off the shelf’ fix. Their website does, however, provide some examples of ideas that work of have been tried elsewhere.

Whether it be a new development, a town centre strategy or investment in existing public spaces, what is often sadly lacking is sufficient thinking from the perspective of the full range of people who will be inhabiting these spaces. Research, talking to and involving those people who may be future users of the space should be a standard part of the approach to planning for investment in the public realm, as well as on going monitoring and investment.

Many people with many needs can be overlooked when places are designed for a hypothetical average standard model. People are not standard, and the lens of a child is a helpful one as planning and designing for children will often result in places that are more accessible and more equitable for everyone.

By Jen Heal

Footnotes:

[1] https://www.urban95academy.org/home

[2] https://www.playwales.org.uk/eng/rightoplay

[3] http://makespaceforgirls.co.uk/

Board member Jon James discusses why we need to refurbish and repurpose buildings rather than bulldozing to make way for new developments. You can read his blog here:

Sense of the past with a commitment to the future – Jon James

https://gov.wales/kick-start-new-welsh-schemes-heat-homes-and-businesses-using-city-centre-heat-networks

Carole-Anne Davies, Chief Executive of the Design Commission for Wales has welcomed the publication of the interim report of the South East Wales Transport Commission . She said: “The South East Wales Transport Commission is considering how to reduce congestion, aid connectivity and demonstrate the need to consider transport and land-use planning comprehensively.

“As the Design Commission for Wales, we fully support efforts to align transport and land-use planning fully and strategically. As demonstrated in our collaborative 2019 Transit Orientated Development charette, we are working with Welsh Government, the Cardiff Capital Region, local authorities and Transport for Wales to help ensure that future investment in placemaking is well coordinated and aligned.

“Our work on placemaking through the Placemaking Partnership and emerging Placemaking Charter highlights the location of development and a movement hierarchy that promotes active travel and public transport as critical elements for success. It is, therefore, encouraging to see the emerging recommendations seeking to establish a network that will increase the modal share of public transport and active travel in the region, making it an attractive and viable alternative to private vehicle use.”

You can read the interim report here https://gov.wales/south-east-wales-transport-commission-emerging-conclusions

Jen Heal, Design Advisor at the Design Commission for Wales has welcomed the publication of Building Better Places. She said: “The planning system can help deliver a more resilient and brighter future for Wales.

“Recent months have shown us just how places and placemaking can make a real difference to our quality of life, our well-being and our economy. The planning system is central to this so we very much welcome the publication and confirmation of the commitment to quality and placemaking.

“As the Design Commission for Wales, we continue to work with design teams, local authorities, and developers to help deliver better places through good design. This includes our work with Welsh Government on the development of a specific strategic design review service for local development plans to ensure that strategic placemaking decisions help achieve the best outcomes.

“We’re also continuing to support the Placemaking Wales Partnership. In all our work right now we are also aiming to apply what we’ve learned throughout the most difficult months and promote better outcomes for all as we work together with Welsh Government to assist recovery.”

The Welsh Government publication can be read here.

Please see below link to the DCFW response to Public Consultation Cardiff University CSM Building August 2018.

DCFW Response to Public Consultation Cardiff University CSM Building

Please see below the DCFW response to the National Assembly for Wales Consultation: State of Roads in Wales.

Ysgol Bae Baglan by Stride Treglown wins Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture

Public value should be the primary objective of any investment of public funds and resources in any project, shouldn’t it? Now more than ever we need to recognise that quality and adding long-term value matters more than short-term capital cost. The latter is perhaps even the critical factor that drives value down and undermines the power of the public purse. Public value matters because people and communities – the public – matter.

In a context of uncertainty and budget cuts, it is easy for governments and local authorities to be tempted by lowest cost options now, with insufficient regard to the problems and costs they may store up for the future. The financial cost of designing and delivering a new building, for example, is easy to measure – a sum of the fees, material and labour costs. However, the true value and cost of that building over its lifetime is much more complex to understand and cannot be simply represented by a number. Designers are continually challenged to achieve more with less – arguably it is their key skill. Decision-makers must take responsibility for understanding and meaningfully assessing the whole-life costs, value and impacts of publicly funded projects, irrespective of how well supported they may be to do so. Cheap, political quick-fixes are not a good solution.

The cost of poor quality

Poor quality buildings will cost more to operate due to higher energy use, demanding maintenance requirements and the need for more frequent replacements and repairs due to lack of durability. Poor quality places undermine health, well-being and productivity which, in turn, places greater strain on public services. And, if bad design means that a facility is not fit-for-purpose or is underused because it is unattractive or uncomfortable, the investment will not have been good value.

The value of good design

We know, and have known for a very long time, that well-designed, quality buildings and places represent good value for public money. Durable, good quality materials and carefully designed details reduce maintenance and repair costs. Well-planned and integrated environmental strategies minimise energy consumption and cost and create comfortable, healthy environments. Countless studies show that good building design can reduce the recovery times of hospital patients, increase the productivity of workers and help children concentrate better at school. Good quality streets and public spaces can encourage walking, cycling and other activities and foster an environment for social interaction.

Moreover, investing in quality in the public estate is symbolic of the value we place on people and their communities. What kind of a declaration do we make when we default to the cheapest solution, regardless of its potentially detrimental impact? Public spending must demonstrate responsible, resourceful, good value investment.

Investing in the design process

The good news is that quality public buildings and places don’t need to cost significantly more to deliver and provide significantly better value for money in the long-term. Investing in a talented design team and affording enough time for early design processes are key to unlocking this value.

Sunlight, daylight, fresh air and good views are freely available and contribute to well-being and sustainability. Good designers will make use of these natural resources to minimise energy demands and create comfortable, delightful buildings and places that stand the test of time.

Good designers are creative problem solvers and will aim to find the best value solution within a given budget and set of constraints. Having a multi-disciplinary design team working on the project from the outset will ensure that different problems are tackled in an integrated way. Meaningful engagement with clients, building users and members of the public helps designers identify constraints and opportunities and allows them to shape the brief and response for the project.

Complexity in buildings adds costs. Intricate junctions are more difficult to build and complex mechanical services can be more expensive to run and are more likely to attract maintenance costs. Good designers simplify without compromising function or beauty; but simplification requires time and skill.

A good design process involves a cycle of testing ideas and refining the design in response to the results, leading to better understanding of how a building will perform over its lifetime, reducing risk.

Good design takes time and skills. Cutting costs and reducing investment in design reduces quality and value in the long run.

An encouraging winner

This year’s Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture winning project, Ysgol Bae Baglan is a case in point. Designed by Stride Treglown Architects, the so called ‘super-school’ provides for children from age three up to 16. The Gold Medal, supported by the Design Commission for Wales, recognises architecture as a vital element in the nation’s culture and celebrates architecture achieving the highest design standards. Encouragingly, this year saw a higher proportion of publicly funded projects entered and short-listed than recent years.

© James Morris

Judges praised the winning scheme for the aspiration to unite a local community which suffers from high levels of deprivation. The approachable and welcoming building provides a focus for the community and offers facilities for everyone to use, so that the whole community draws value from the school.

The classrooms are spacious and abundant with natural light, and the architecture provides inspirational spaces for play and learning. A central stage allows for arts, performance and gatherings; for a shared environment where lives and their potential are shaped.

© James Morris

Ysgol Bae Baglan encapsulates the aspirations of the school and the wider community and, through good design, delivers quality and represents good value for public money which no arbitrary capital cost cap and truncated design process will ever reflect or enable. Prudence does not reside in the cheapest or the fastest. Public investment should focus on public value. It should say ‘we value these communities, these children, these people.’ It is entirely possible, and should be the norm, to set out and adhere to realistic timescales, budgets and value-driven objectives, in a clear vision for the outcomes we wish to result from our investment. Let us not only aspire, but commit to make every publicly-funded project in Wales worthy of an award for design quality and public value.

Written by Amanda Spence, Design Advisor at DCFW

By Efa Lois Thomas

On the 2nd of March 2017, Hatch members came together with Young Planners Cymru for an event at DCFW that provided and opportunity to explore the potential of the National Development Framework (NDF). It was particularly interesting for me, as I come from an architectural background, not a planning one, but I thoroughly enjoyed it. It was interesting to think that the preparation of this plan could have real impact on what happens on the ground in Wales in the next 20 years.

The presentation began with an explanation of the National Development Framework, how Wales needs an overarching vision for planning, how we want to create change in our communities and what makes a good place. We also discussed how Planning Policy Wales will be reviewed and integrated with the NDF.

We then split into two workshop groups, one discussing the National Development Framework and the other thinking about the objectives of planning and sustainable places for Planning Policy Wales.

The National Development Framework workshop considered the 20-year national development plan (which will replace the Wales Spatial Plan) and the key issues that face Wales now and in 20 years’ time . Some very interesting ideas were discussed including: the inherent potential in linking the NDF to the Well-being of Future Generations Act and Active Travel Act, how large nationally important projects might be reflected and, on a smaller scale, how every town and village could have safe routes for people to walk to amenities, and how the focus should shift to more sustainable travel methods, such as cycling or trams.

We also discussed how the character of some towns is being slowly eroded by the impact of national retail chains, resulting in the closure of local independent businesses and the loss of a sense of ‘place’.

The potential for Wales to increase and improve its tourism industry, through better marketing and planning emerged as a key theme. We discussed how some towns outside of Cardiff have tourists commuting from Cardiff to get there, just because there aren’t enough hotels in the capital. We also considered how the protection of historic Welsh place names could potentially become part of the NDF as they are something completely unique to Wales, which is a perfect opportunity for marketing tourism.

On the subject of decarbonisation, we discussed exciting opportunities presented by the tidal lagoon projects, as well as how the devolution of control over natural resources could affect Wales’ carbon output. It was also raised that, in an ideal world, there should be financial incentives to reinsulate existing housing stock as the ineffective use of energy greatly affects the amount of carbon that is used.

We also briefly explored the potential of re-wilding Wales’ farming landscapes and the impact of changes following departure from the EU.

After half an hour, we swapped workshop groups to go to a workshop on Planning Policy Wales.

This was much more focused on the potential of what the Planning Policy Wales specifically could do to rectify the problems that Wales currently faces.

We discussed how planning should operate, for example, whether putting planning notices on lampposts is an outdated custom. The issue that current demographics that are usually consulted in planning are either those over the age of 65 or school children was raised and we considered what could be done to rectify this.

A complicated issue that emerged was how to give a town or area that arises from a new development ‘soul’ and ‘community’. We discussed how some areas on the outskirts of Cardiff only have two supermarkets, a school and a few housing complexes and what could be done to make this place better.

We then had a discussion about why people wouldn’t want to live in certain areas, and what makes people feel safe in a particular area. I was personally reminded of Jane Jacob’s theory in ‘The Life and Death of Great American Cities’, about having eyes on the street, and people feeling ownership of the street. We explored what makes us personally feel safe and what may deter us from walking somewhere, but feel perfectly comfortable in a car or a bus. We then considered whether improving the safety of some areas would make people want to live there.

The evening concluded with a brief Q&A session with the representatives from Welsh Government’s Planning Division. It was an enlightening evening and it was very exciting to see what could potentially be shaped into the Welsh landscape over the next 20 years.

Efa Lois Thomas is at Part 1 Architectural Assistant at Austin-Smith:Lord and Winner of the National Eisteddfod Design Commission for Wales Architecture Scholarship 2016.

The Planning Directorate at Welsh Government has begun work on the production of a National Development Framework (NDF). The NDF will set out a 20 year land use framework for Wales to replace the current Wales Spatial Plan, and provides an exciting opportunity for good design to add value through a coordinated approach. In a response to a recent call for projects, the Design Commission for Wales submitted a proposal for a national tourist route for Wales.

Download the full proposal here: DCFW’s Welsh Ways NDF Project Proposal

Coordinated by the Design Commission for Wales, Welsh Ways is a proposed Wales-wide project which will harness the power of good design and planning to enhance people’s experience of the magnificent landscapes in Wales, whilst adding value to the tourism industry and rural economies.

The project will identify and promote scenic routes around Wales and commission interventions along those routes which engage people with the landscape and its natural resources and heritage.

The routes will allow for a variety of travel modes, including driving, walking, cycling and public transport options, with interventions including viewing areas, picnic spots, rest areas, public toilets and transport stops. Each intervention will be carefully designed in response to a deep understanding of its place in order to showcase the beauty of the landscape setting, design talent and craftsmanship.

To achieve best value from the project, a number of organisations will collaborate to coordinate the various aspects of the project which will be led by the Design Commission for Wales. The ethos of the project closely follows the seven goals of the Well-being of Future Generation (Wales) Act, by addressing issues of economy, resilience, environment, tourism, culture, heritage, health, community and inclusivity. The commissioning of design and construction teams for each of the interventions will encourage innovative and collaborative practice, supporting and promoting design talent.

As a core project of the Wales’ National Development Framework (NDF), Welsh Ways provides a useful strategic, nation-wide project which meets Welsh Government’s objectives for sustainable place-driven planning with minimal capital investment. Welsh Ways can be used as an exemplar early-win to demonstrate the value of the collaborative, integrated, strategic approach to planning and place-making in Wales endorsed by the NDF.

Download the full proposal here: DCFW’s Welsh Ways NDF Project Proposal

The latest Hatch event involved a walk around Cardiff Bay, guided by urban designer Dr Mike Biddulph, from the Place Making team at Cardiff Council. To reflect the range of built environment disciplines represented in the Hatch network we have collated the perspective of an urban designer, arts consultant, public engagement and experience design consultant and an energy and building physics engineer to see how their views on the event varied.

Emma Price, Arts Consultant reflects on an illumination of Cardiff Bay and the common aspects of seemingly different disciplines.

I was not sure what to expect at the latest Hatch event as I am not an urban designer, landscape architect, planner, or architect. So when it was my time to introduce myself, I hesitated, before revealing that I am an arts consultant working predominantly in commissioning art in the built environment. It is my professional experience in this field which therefore framed my interaction with the workshop.

The walk and talk brought together a range of designers and innovators working in the city. Mike set out the challenges of urbanisation and the creative potential of speculative design. We collectively examined the constraints and areas for potential development; exploring the physical factors that can affect development prospects, and the potential for urban design solutions for an ever evolving Cardiff Bay

I learned that urban design is a particular form of enquiry into the nature of our city, its form and function. We all seek to understand the city as a place of human coexistence and to contribute to the creation of strategies and projects that inform its future development. This struck me as similar to the new and innovative ways that artists are approaching working in the public realm.

We were encouraged to look for and explore new ideas around the design decisions faced by Mike and his colleagues when developing an urban space that works for a wide section of the local population and visiting community.

During our walk we explored and reimagined the Bay through its physical landscape and its role in cultural regeneration. The discussions reminded me of the Situationists and their interpretation of psychogeography. This is something that I have long been interested in, but until now, only from the perspective of working with artists to investigate the experiential and physical elements of place making. But in fact we are all, in some way, psychogeographers.

Psychogeography and the dérive

…The Situationists’ desire to become psychogeographers, with an understanding of the ‘precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals’, was intended to cultivate an awareness of the ways in which everyday life is presently conditioned and controlled, the ways in which this manipulation can be exposed and subverted, and the possibilities for chosen forms of constructed situations in the post-spectacular world. Only an awareness of the influences of the existing environment can encourage the critique of the present conditions of daily life, and yet it is precisely this concern with the environment, which we live, which is ignored.

(Source: Plant, S. (1992) The most radical gesture: The Situationist International in a postmodern age’ P58: Routledge.)

Mike enthused us as to the benefits of walking through a place with eyes wide open, and the need to truly address and represent contemporary urbanism in future plans. Mike also brought home to us the challenge in resolving complex issues facing transport, public space (including streets and land use), and building typologies through creative design plans.

The group’s critical contribution throughout the walk paid homage to the importance of cross-sector consultation, mirroring Mike’s generous, site-specific explanation of the work of urban designers in creating our streets, buildings and transport routes that consider both people and place.

Although I had worked in the Bay for several years, I was now seeing the Bay’s streetscapes in a new light. Perhaps we are so tuned out and focused on travelling through places for practical reasons that we don’t pay sufficient attention to our journeys – on foot, via varying modes of transport, or via our creative imagination. The workshop highlighted that fully engaging our senses and emotional awareness on something as basic as a short walk can be used to positively influence place.

As the site-responsive workshop progressed I felt increasingly at ease with the contributions I could make when discussing potential opportunities in line with the cultural heritage and future aspirations for this part of the city. This comes from working with artists, many of whom, through the context of their practice, research place, people and the cultural offerings of a particular site and whose work directly or indirectly offers creative development opportunities. So, not too dissimilar to that of an urban designer.

John Lloyd, Energy and Building Physics Engineer, enjoys the bigger picture offered by urban design.

Coming from an engineering background, I must admit to being a little in the dark as to exactly what Mike’s line of work as an Urban Designer entailed, so before arriving did a little internet search, turning up the following:

Urban design is about making connections between people and places, movement and urban form, nature and the built fabric. Urban design draws together the many strands of place-making, environmental stewardship, social equity and economic viability into the creation of places with distinct beauty and identity. Urban design is derived from but transcends planning and transportation policy, architectural design, development economics, engineering and landscape. It draws these and other strands together creating a vision for an area and then deploying the resources and skills needed to bring the vision to life.

(Source – http://www.urbandesign.org/)

As interesting as that sounded, I still was still a little vague on the specifics so went along with an open mind and no preconceptions. To all of our surprise, Mike Biddulph chose to focus on the area of the Bay where Lloyd George Avenue connects Bute Street and Roald Dahl Plas. Hatch members in attendance initially struggled to visualise the development of a site, which on face value, appeared to be an area of the city that was already “complete”, modern and a significant part of the local road network. After some encouragement or perhaps coercion, we all came to agree that while the area may not require redevelopment, it is underutilised space in a prime location and the focus of the evening’s conversation therefore centred on how it might be improved.

This is one of the parts of Cardiff that has seen substantial change over recent decades, but there is scope to think about it differently if infrastructure projects such as a South Wales Metro system extends down to the Bay. Routes can be found to better link Cardiff Bay to other areas of the city and one of a number of routes could bring a tramline through the road network around Craft in the Bay and the Red Dragon Centre. If this were to go ahead then the significant construction work required would in itself bring opportunities to redesign and make better use of the spaces around this area; most of which is currently uninviting to pedestrians and therefore arguably a poor use of such large open public space.

While the Hatch group is made up of a fairly diverse set of disciplines, all of which demand a degree of creativity, I think it’s fair to say that most of us rarely need to operate on the scale and with the lack of restriction that Mike’s job demands. As an Energy and Building Physics Engineer, I’m usually focussed on small details and technical calculations and personally found the lack of constraints on Mike’s current work as quite liberating, if perhaps a little overwhelming!

From our starting point at the Millennium Centre, we walked along an old footpath behind buildings facing onto Bute Street, leading to the old derelict train station building. Mike chatted though how he would think about such an area, including ideas for how this listed building could be brought back to life and how, on the back of this, the Council could try to influence further development of this area.

We walked along Bute Street to discuss the importance of the Loudon Square development, how Bute Street could potentially be opened up to allow access across to the Lloyd George Avenue area and the benefits this could bring to the Butetown community. Finally, heading back towards Bute Place for a closing conversation bringing together all that had been discussed, Mike worked through one possible vision for how this part of our city could look in the future.

One of Mike’s opening lines at the start of the evening was that he thought that his was the best job in world. By the end of the evening and now with a better understanding the full scale of the positive influence someone in his position could have on the future of our city and its communities, I think he might have a point!

Peter Trevitt, Public Engagement and Experience Design Consultant, on the importance of someone looking at the bigger picture.

Gathering outside the Wales Millennium Centre (WMC), Mike set out to provide a flavour of what his work as an urban designer in the local authority is all about, by taking us on a journey around his mind, as well as the Bay. He then surprised us when he asked us which part of the bay we thought he was thinking about at the moment. We all assumed it would be one of the obviously run down or under-used areas, but in fact his focus is on the relatively well-kept area between Lloyd George Avenue and Roald Dahl Plas.

Mike explained that his work involved thinking long term about the big picture, and that it was a fluid process of exploring how even quite radical changes and options might work and being prepared to reconsider them as often as necessary. It was as if in his mind he has a big pencil and eraser does endless sketches of road layouts, development blocks and landmark features, using his skills to find interesting configurations. He works with other specialists at the Council to provoke wider discussion and consultation, long before a scheme is formally defined.

This strategic approach felt very appealing, but also very necessary – if no one is considering our environment in this way, how can we be sure that the best solutions are being found at an early enough stage?

Continuing our walk there were more surprises in store. We quickly found ourselves on a long footpath following the line of the old dock boundary that most of us had never seen before, and provided a new angle on very familiar sights. We looked at the old Bay Station building and then explored more of Bute Street, as far as the potential cross-route to the south of Loudoun Square. Mike explained that if a tramline comes to Cardiff Bay, this could become a key point to provide a new east-west route in Butetown. We began to appreciate better how his mind worked now, always looking for the links and connections that were key to opening up the city and attracting investment.

This fascinating walk ended back near the WMC drawing tram stations on a large piece of paper on the floor, and debating the merits or otherwise of whether high rise development could even be accommodated in this area or not. Mike had said he loved his job, and it was not difficult to see why.

Lindsey Brown, Urban Designer reminds us of the importance of ‘looking beyond’ ourselves and our everyday, and to future legacies.

As an urban designer it is almost impossible not to stand in a public space or on a street and refrain from analysing the urban fabric, watch what people do or wonder why all the seating has been positioned on the shaded side of the street. We’re never off duty! So when the invitation arrived to join Hatch’s latest event exploring development and placemaking around the Bay, it went straight in my diary!

Meeting outside the Wales Millennium Centre Mike began the workshop by asking us what we thought of the space around us. There was a suggestion it was the culmination of the Bay’s transformation; once a redundant and inaccessible dockland, now a popular destination for visitors and residents of Cardiff. There was discussion too on the connection between the city and the Bay, focusing on Lloyd George Avenue, its poor level of use and disjointed links to the city centre. Mike immediately turned this on its head and asked us whether this is really the burning issue for the future development of the Bay? His assertion being that Lloyd George Avenue exists and people do use it to walk, cycle and drive between the city centre and the Bay. Instead he posed a different question; what connections and opportunities in the Bay have not yet been realised? And so the tone for the evening’s workshop was set – where is the potential in the Bay and how, as designers, can we shape its development?

We focused on ‘The Flourish’, the rather large traffic island home to a Grade II listed building housing Craft in the Bay. Mike led us along a narrow path, edged by original dockland railings. It forms one of the many north–south linear routes in this part of the Bay, but it was the opportunity to introduce east-west connections and bring together the dotted collection of galleries and art spaces that appealed to Mike.

Heading further north talk of unrealised opportunity went up a level. We gathered on Bute Street and Mike asked ‘What about punching a hole through this wall?’ The wall in question being an 8ft stone wall bounding the railway track. Whilst eyebrows were raised, eyes also lit up!

We walked through Cardiff Bay railway station and Mike mentioned the possibility of a tram and the opportunity to extend the line to the Flourish. An opportunity to not only create a sense of arrival befitting of the Bay but improve connectivity for everyday passengers and visitors alike.

Stretching alongside the railway line we touched on Lloyd George Avenue and how introducing a tram line would create opportunity for new building lines and streets that would add layers to the Avenue rather than erode people’s patterns of movement.

Our final stop brought us to the traffic island in the centre of the Flourish and it was here that a blank plan was cast on the floor in typical urban designer style. Thoughts and ideas from the discussion were quickly sketched, bringing to life the opportunities and potential we had spotted during our walk. For me it was an inspiring and somehow reassuring experience. We are all familiar with plans and drawings but so often we don’t get to see the journey of how we have arrived at the design on the plan.

The event came with the brief ‘to be prepared to look and talk’. This reminded me of an urban design phrase I often use when exploring the built environment, ‘look up, around and along’. For me Mike’s workshop has added a fourth dimension to this: ‘look beyond’. To remember that as designers we are not just here to celebrate the good and undo the bad but to realise the potential.

Samuel Utting, Architect welcomes the opportunity to think more strategically.

From an architect’s perspective, the workshop was an opportunity to better understand the thinking processes and frames of reference of urban designers, who generally operate at a more strategic level and within longer timescales.

As we were gathering in Roald Dahl Plass to start our workshop, Mike asked what we thought of the space. Although it is a place quite familiar to us all, it wasn’t easy to pinpoint why we weren’t instinctively in love with the space. The solutions to transforming it into a successful public square became clearer as we walked through the area with our guide, reorganising it and solving its issues in a piecemeal way. Talking and walking around Butetown and Cardiff Bay was a welcome reminder of the principles behind successful urban spaces that the likes of Jane Jacobs, Jan Gehl and William H Whyte introduced to us in architecture school. It was good to see these principles in the future vision of Butetown and Cardiff Bay… at last.

Thank you to all of our contributors.

DCFW Hatch member, Elan Wynne, reflects on Hatch’s evening with the Policy Makers

…Who are these people that make the decisions on what can and can’t be built, and what guides their decision making? This is a question often asked by designers of all disciplines and their clients as they navigate the statutory requirements, the planning system and the impact of policy.

The most recent event organised by HATCH, presented an opportunity for designers working in the built environment to hear from ‘Them’; the experts who are driving, influencing, changing and upholding current planning policies. And guess what? They came across as being passionate about doing what was right for the community as a whole at a local, national and international level.

The evening covered the hierarchy of policy and planning through presentations from the following speakers:-

- Gretel Leeb, the Deputy Director of the Environment and Sustainability Directorate at the Welsh Government on the Well-being of Future Generations Act (Wales) 2015

- Stuart Ingram, Senior Planning Manager at Welsh Government on the Planning Act (Wales) 2015, and Planning Policy Wales

- Judith Jones, Head of Planning at Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council on Local planning policy

The night was kicked off by Gretel Leeb’s heartfelt presentation on the Well-being of Future Generations Act (Wales) 2015 (FGW). We were introduced to this recent piece of legislation which aims to encourage ‘joined up thinking’, and is one of the first of its kind. The FGW Act will call on public bodies in Wales to find ways to meet all of the 7 goals identified in the Act, working together toward a more prosperous, resilient, healthier, equitable country that has more cohesive communities, a vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language, and is globally responsible. Gretel viewed the role of designers, as specialists in problem solving and joined up thinking, as vital in helping to achieve the goals and positively influencing the construction industry. Gretel reminded us of our capacity to enthuse and educate people through the way that we design.

Stuart Ingram of the Welsh Government Planning Directorate, presented a very clear account of what national planning policy is, and how it works at a national level. His role includes briefing, advising and preparing information for Ministers, who when they speak on an item in public, may be seen to be making policy. Stuart is one of the team that helps shape, communicate and monitor policies that are made, ensuring that they are evidence based and made in the best interests of the people.

Policy making in this country is of course part of a democratic context, and if not perceived as the speediest of processes, provides time for anyone who is interested to be properly consulted, informed and involved. Inevitably, policies made will not please everyone, but through the careful practice of identifying a need, evidence gathering, developing, consulting, adapting, implementing and monitoring, it is now said that we have a good track record of evidence based policy making in Wales.

Decision makers undertake a balancing act to ensure that one policy doesn’t clash with another. There may complexities that challenge good intentions. For instance, planning for the natural environment and local carbon reduction might not always be a harmonious match; wind turbine farms or photo voltaic arrays might be not always be appropriate to a local natural environment or its immediate community. As new challenges become apparent, new policies have to be made to address their effects. Like the editor of Vogue magazine, people like Stuart have the continual task of keeping on top of emerging trends, so that we can be safe in the knowledge that our country can cope with the latest land use issues.

Judith Jones discussed, what was, to me, the more familiar side of how local planning policy is utilised, and how it guides planning departments and designers alike in the parts they play in the continually developing built environment. Her references to Patsy Healey’s lecture at the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape at Newcastle University in 2011, Civic Capacity, Progressive Localism and the Role of Planning, addressed the responsibility of society to engage in the process, as well as planners’ roles in providing ‘explanations not just of how formal regulations work, but why it has evolved and what value it carries’.

Judith went on to discuss how emotional attachment to an area or building is often not considered as important as it should be, and that design and planning processes and policies can at times fail to address this fully. And yet emotion is still part of the decision making process at a certain level, where a planning applications can be decided or influenced by an officer’s preference. It is a difficult task that planners face, this balancing act; and alongside local policy which sets out the fundamentals, such things as ‘material considerations’ can also become grey areas. Weighing up considerations can often be influenced by the responses received from those that are consulted. This highlights the need for an early local voice, getting people in the community involved so that the community affected can be part of shaping their own environment. Whether the disillusioned voice of many is a good thing against the inspired thinking of a few is something we at HATCH have all discussed before and I’m sure will come up again. In this age of social media and global trends, an up to date local policy has an important role in regulating the evolution of the environment in which we live, which is happening at lightning speed.