Placemaking, Climate Change and the Routes to Net Zero

In October 2021, DCFW and the RSAW hosted a joint event titled ‘Climate change and the Routes to Net Zero’. Three of DCFW’S Design Review Panel members spoke at the event – Ashley Bateson, Lynne Sullivan and Simon Richards.

Ashley Bateson is a Partner and the Head of Sustainability at Hoare Lea. Ashley works with clients and architects to improve energy efficiency and achieve broader sustainability objectives. Ashley is an expert contributor to a number of organisations and government research and reviews, is an active member of the UKGBC and a member of the Design Commission for Wales Design Review Panel.

Lynne Sullivan OBE is an architect at LSA Studio. A consistent theme in Lynne’s work has been built environment sustainability, through the buildings and places she has designed and delivered, and through research and advisory roles. Lynne is a Visiting Professor and design consultant, including as a Design Advisor for RIBA Competitions and a Design Council expert. Lynne authors and chairs policy review and research projects for UK governments and others, is a Board member of the Passivhaus Trust and the CLC’s Green Construction Board, Chair of the Good Homes Alliance and a member of the Design Commission for Wales Design Review Panel.

Simon Richards is the Founder Director at Land Studio. He has spent over fifteen years leading design teams and projects on a range of sites throughout the UK and internationally. He is also a panellist and Co-Chair for the Design Commission for Wales and a panellist for the Chester City design review panel.

In this article they revisit some of the key themes raised in the event.

Ashley Bateson:

Climate change will impact the built environment in many ways. We have already seen significant trends in the last ten years: heat waves, more extreme weather events, storms, and flooding. Yet our way of planning and designing buildings hasn’t changed much. Architectural priorities, engineering methods and construction standards haven’t altered during this period, or indeed for decades, despite the well published science on the consequences of global warming. We need to fundamentally embed climate resilience in how we plan and design, in order to limit the detrimental impacts on properties, people and infrastructure.

New buildings should be designed to limit overheating risk. Measures such as designing appropriately configured glazing (with limits on full height glazing), providing more openable windows that allow purge ventilation and shading, where appropriate, can avoid overheating conditions. External environments should incorporate nature-based solutions to moderate microclimates, absorb rainfall and create cooling conditions in the summer.

Many of these techniques are not new and well recognised in traditional architecture. Even though we know that temperatures are predicted to rise, we see new homes, schools and offices that don’t have sufficient means of limiting solar gains or providing adequate ventilation. In some cases, the conditions become unbearable, and these buildings become difficult to occupy. Some local authorities require designs to be informed by thermal dynamic modelling and expect overheating risk assessments, but most planning authorities don’t have a policy for this, so non-resilient designs are being developed without proper reviews.

If we make climate resilience a priority in planning and design, we can deliver a better quality of life for occupants, reduce costs of repairing damage and reduce the need for more expensive mitigation later. Internationally it’s not a new experience. It’s a great opportunity to see how other countries deal with hotter summers and wetter winters and learn design lessons from them.

Lynne Sullivan:

Following COP26 in November 2021 even the UK - with its world-leading 78% reduction in carbon emissions by 2035 ambitions - must revisit and strengthen the policies needed to meet targets agreed in Paris 2015. For the built environment sector, which is responsible for 40% of our carbon, this means radical change.

Our sector’s role in placemaking is key to linking the range of strategies needed to rise to this challenge. For example, if you analyse carbon footprint on a local/regional basis, transport always represents the biggest portion, so designers must advocate reducing transport emissions by location, amenity, and connectivity choices.

The design of buildings must be holistic: accurately predicting the carbon footprint of buildings over their lifetime demands a cultural re-think for our industry, favouring sustainable re-use of existing structures and materials, as well as driving down energy demand to a level consistent with our Paris commitments, and ensuring performance in use matches prediction. It is estimated that 40% of existing UK homes overheat and, in a warming climate, shading and the ability to minimize excess temperatures is a crucial aspect of building design but also demands design of public space and streets to mitigate high temperatures and damaging health impacts.

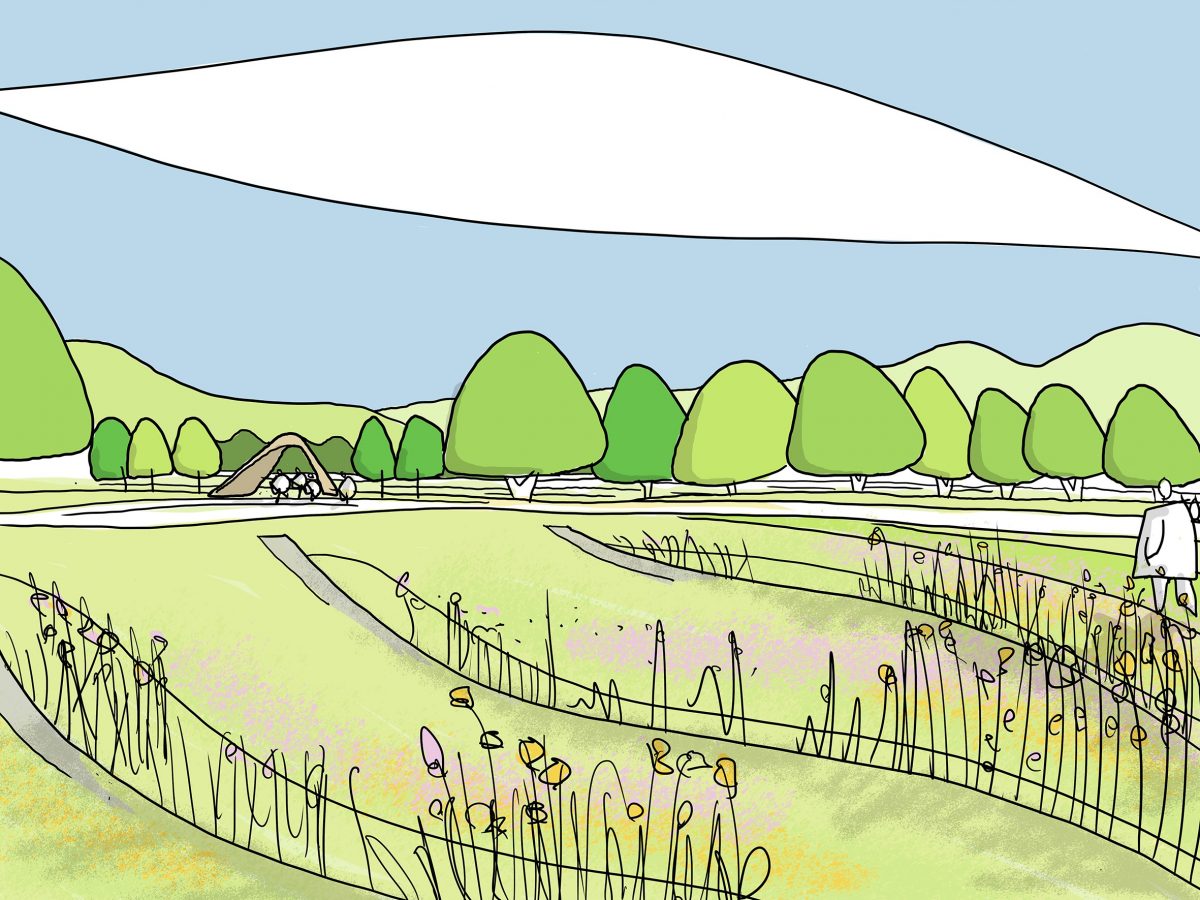

Well-designed green spaces are proven to reduce ambient temperatures as well as providing health benefits and socialising possibilities. Welsh Government has committed to plant 86 million more trees in Wales, and in December 2021 announced that every household in Wales will have a tree to plant, either at home or in their community. Designers can deploy these initiatives to draw together a progressive vision for built environment developments, to improve and create places which are attractive, therapeutic, and resilient.

Technology is our friend in this endeavour: world class public transport infrastructure ensuring green travel and inclusive access is of key importance, and on-demand autonomous private and shared infrastructure is now on trial in the UK. Digital Building passports are being rolled out as part of Welsh Government’s Optimised Retrofit Programme, paving the way for all buildings new and existing to have a digital ‘twin’ to track materials, maintenance, and performance, offering every building user a digital ‘app’ interface which enables them to track air quality and energy data – real-time evidence of design outcomes!

Simon Richards:

Reconnecting people with nature is vital to tackling the impact of global warming.

Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution and the gradual urbanisation of the natural environment, we have become increasingly detached from nature. Sadly, too many of us have little or no understanding of the natural processes and cycles that surround us. It has led to a dangerous lack of understanding and care for addressing the problems we have created. For too long, we have been working against nature rather than with it.

So, what can we do to address the awareness of climate change in today’s society and what should the landscapes of the future look like?

I believe that if we re-connect with natural process, we will enhance biodiversity, reduce flood risk, sequester carbon, and create a more resilient food-producing landscape. As designers, we should seek to embed nature into our designs, whether we are designing a landscape for a school, a residential street, or the re-interpretation of a National Trust property.

The water cycle is a key component of our landscapes that also needs to be addressed and fully integrated into our built environment. Enhancement of watercourses and de-culverting of drains are integral to healthy habitats and visible nature.

The re-establishment of ancient water management practices through rain gardens, woodland management and, critically, the siting of new development helps to create a resilient natural environment whilst demonstrating to people the positive value of water in our landscapes.

As designers, we could begin to specify some exotic planting. Highly flexible, these plants are good at responding to unusual environments more quickly than our native plants.

It is important that we choose ethical and environmentally sensitive materials with a low carbon footprint. We should also look at calculating, reducing, and offsetting our carbon in a meaningful and long-term way.

The health of our soils has long been a forgotten component in our landscapes, but it forms an integral part of a successful rehabilitation of the natural environment and the enhanced sequestration of carbon.

Nature should be at the heart of practice. If we enable people to have a better understanding of the importance of nature, then we have a greater chance of successfully tackling the challenges of our changing climate.