Category: Uncategorized

Placemaking as a way of working

Jen Heal, Deputy Chief Executive of the Design Commission for Wales

The last six editions of the Placemaking Wales Newsletter have covered each of the six principles of the Placemaking Wales Charter in turn, with articles from a range of contributors covering street design, pop up uses, strategic planning and more. However, it is important to ensure that we don’t get into the habit of separating out different aspects of placemaking too much or we risk falling into the old way of doing things. The new way of doing things – the placemaking approach – is about joined up thinking, addressing the place before the disciplineand breaking down silos. It is about a way of doing things as much, if not more, than the physical result at the end. This is the theme that we are covering in this edition, looking at how people are changing their way of working to integrate placemaking as a process, or ideas of how further change is needed to address current weaknesses.

The Placemaking Wales Charter was launched nearly four years ago and, with over 150 signatories across a range of disciplines in the public, private and third sector, its principles have become more embedded in everyday practice for many organisations. However, there is still much progress to be made to embed placemaking as a way of working across all organisations from Welsh Government to local authorities, developers and practitioners.

In particular the following placemaking concepts need to be more engrained as part of everyday practice:

- Public participation as the foundation of the placemaking process – this is where the true success of the process lies in terms of investing in the right physical changes to a place but also to maximise the benefits of active engagement and involvement from local people.

- Breaking down a siloed way of working by discipline to instead focus on specific challenges in specific places.

- Allow time and resources for testing ideas. This helps to explore different options as well as build support before more expensive, permanent interventions are made.

- Develop a collective vision for a place that all stakeholders can work collaboratively towards.

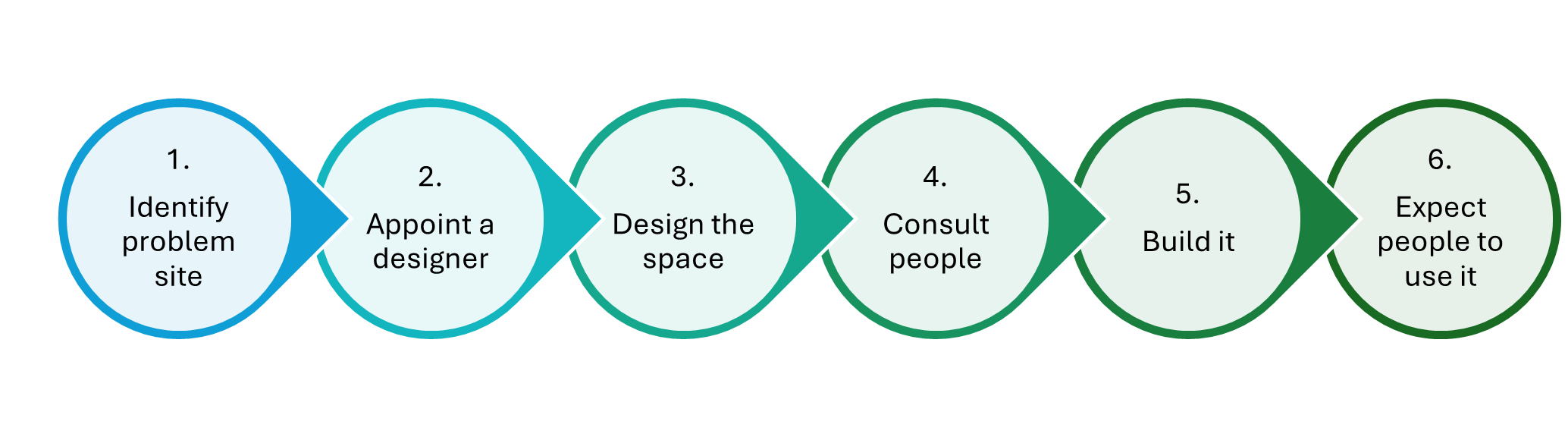

An example of what a shift to a placemaking approach looks like might be in tackling a “problem” space within a neighbourhood. One approach to such a space would be the following:

In this scenario community engagement in the process is limited to commenting on plans developed by people who have limited knowledge of the neighbourhood and how it works. It assumes people will be grateful for significant capital investment in the space and anticipates how people will use it once built. If objections are raised at the consultation stage, the investment in design to date means that there is often an unwillingness to make significant changes, so the consultation becomes about defending the design rather than responding to comments.

A mitigation to the limitations of this approach might be to introduce an earlier phase of consultation to try to find out what people think about the space now and how it might be improved. Such consultations can often be limited in the number and range of people they attract and those leading the project are wary of offering the community a ‘wish list’ that they inevitably won’t be able to fulfil.

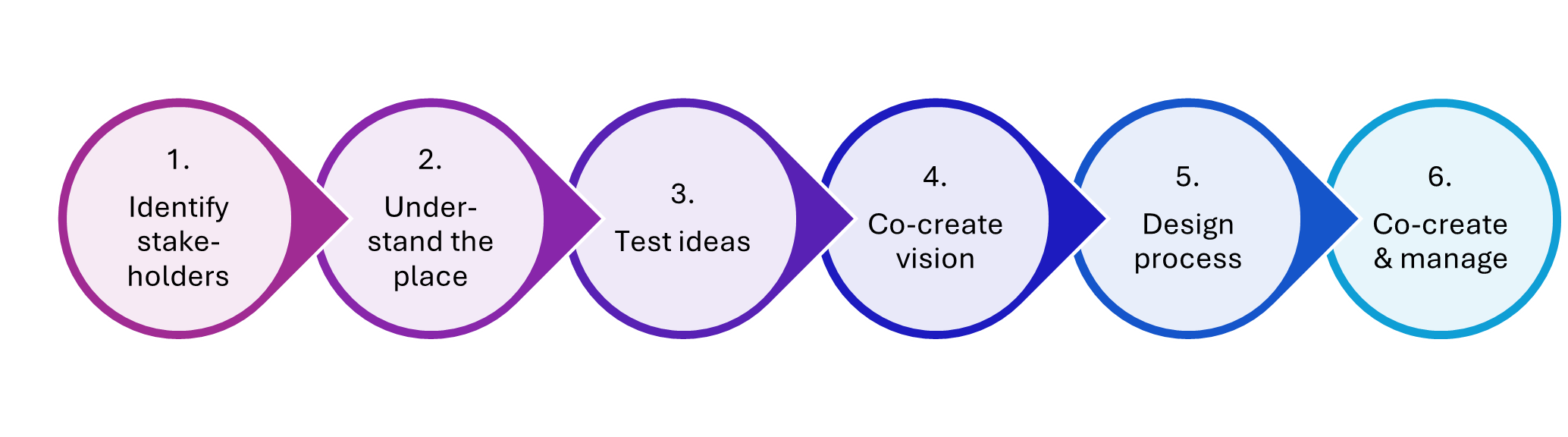

Alternatively, a placemaking approach might look more like this:

The starting point is identifying who has an interest in the location and working with them to understand the place – what works, what doesn’t, what are people’s needs, are there any latent opportunities such as an organisation or business who what to do something in a space. There is then a period for testing ideas where cheaper, temporary interventions are used to see what works in the space, to encourage more people to be involved in its future and to start changing people’s perceptions of it. After this groundwork has been undertaken there will be a much better understanding of what design expertise is needed to support the project. Finally, the space is created with input from the community and their involvement is ongoing through the programming and management of the space.

With a placemaking approach local people are involved from the beginning and are valued as part of the process. The benefits of this include:

- The project addresses the real needs of the community rather than perceived problems.

- The whole process fosters a sense of ownership amongst the community which has benefits for long-term care of the space.

- People make new connections within their neighbourhood which can help create a greater sense of belonging and tackle loneliness.

- The project addresses multiple issues and therefore has multiple benefits for the people in the community rather than a siloed approach that only tackles one issue.

There are certainly challenges to establishing this way of working. Places are complex and we have become accustomed to managing this complexity by breaking places down into separate components and addressing them separately such as health, economic development, planning, sustainability, transport, education, arts and culture. A placemaking approach would need to introduce more complexity by addressing the place first rather than the discipline. This would require different people to work together and a change in the way funding works to ensure that any competition for funding between disciplines is removed. Other matters to address or overcome include:

- The iterative and testing nature of the placemaking approach also requires a different way of thinking about risk. Sometimes things that are trialled and tested may not succeed. This is not a failure but a part of the process of establishing what is needed and what the solution might be.

- Earlier and much more extensive involvement of the people within the place will shift the balance of time, skills and funding more to the front end of a process. However, with more engaged and empowered local people there are multiple benefits at later stages of the process.

- The measures of success may need to change to reflect the intentions of a placemaking approach.

However, these challenges are not insurmountable and can be addressed at a national, local authority and project level by all of those involved in the process if the will is there. The benefits of a placemaking approach could be numerous and the other articles in this edition of the newsletter pick up on some of these opportunities. The challenge to each of us is to think about how we go about doing things differently and working more collaboratively on our next project or initiative.

Jen Heal, Deputy Chief Executive of the Design Commission for Wales

The public realm is likely the first thing that comes to mind when many think of placemaking. A vibrant public square, a bustling high street or a fun-filled local park are just some of the images that spring to mind and are indeed some of the aims of our focus on placemaking. The public realm has many functions to perform and can be a place of delight, but it cannot be considered in isolation. All six of the Placemaking Wales Charter principles are interrelated and need to work together, but the success, or otherwise, of this manifests itself in the public realm.

Conditions to enable a positive public realm

Embedding placemaking into planning policy at the national level through Planning Policy Wales and Future Wales recognises that important decisions that will influence the success of the public realm within a town centre, neighbourhood centre or residential streets are made well in advance of the design of the space itself.

The location of development, availability of choice of movement modes and mix of uses will set the conditions in terms of levels of traffic, opportunities for walking and cycling, and amount of parking needed, all of which influence the amount of space available for public life and the quality of this space. If development is isolated, with no mix of uses and limited opportunities for public transport and active travel, more space will be needed to store and move cars around, fewer people will be out and about and the ‘life’ of the place will be impaired.

Conversely, if new development is situated close to existing facilities that people can easily access via active travel or public transport, or if new development has sufficient density to provide a mix of uses itself, then good design can manage the impact of cars on the environment, and there is potential for the streets and spaces to come alive. More people will have the opportunity to bump into and get to know others in their community, children will have more opportunities to play outside and the conditions will enable healthier movement choices.

Out of the six Charter principles, this leaves people and community and identity. These are two essential ingredients that should inform the design of the public realm to give it distinctiveness, inclusiveness and ensure it meets the needs of the community that will inhabit it.

Public realm as a forum for involvement

The latter two principles above emphasise the role of community engagement in the design of the public realm. Public realm interventions provide the space to test ideas and make changes in collaboration with the community. The prominent placemaking organisation, Project for Public Spaces, has a range of useful resources for placemaking in the public realm with easy to remember headings, such as:

- The Power of 10 – the idea that there should be many (e.g. ten) different things for people to do in a public space[1], or

- Lighter Quicker Cheaper – the promotion of interventions that are implemented quickly to help test ideas and demonstrate how changing a space can help to create a place[2].

It seems that the latter is something that we are not yet very good at in Wales. Whether it is because of the real or perceived barrier of rules and processes to navigate, a lack of skills in this type of engagement or risk adversity, we don’t seem to be able to implement such projects at any kind of pace or scale. Covid recovery interventions exhibited some of this energy, but that seems to have quickly faded away.

I was struck by the example of Milan’s Piazze Aperte ‘Open Squares’ initiative[3], where the city used temporary interventions as a mechanism for engagement and to test ideas before more permanent change. There was an open call to all citizens to identify spaces in the city that could be improved. They used paint to define the public space and put in street furniture to start to establish activity within the spaces and worked with local people on events within the spaces. The feedback from these temporary actions was used to shape more permanent interventions, but the impact was much more immediate: “Every time we closed a street to traffic, children popped up”[4].

An ongoing challenge

The benefits of public realm improvements are numerous, such as encouraging walking and cycling, integrating green and blue infrastructure to manage and mitigate climate change impacts, and providing comfortable, safe and pleasant places to interact with others, thus reducing social isolation. However, that doesn’t mean it is easy. Two particular challenges seem to be prevalent – the cost of maintenance and out of date approaches to highway design. The former threatens the integration of the most basic elements, such as street trees, because there aren’t sufficient budgets or resources to look after them. The latter is an ongoing issue despite a decade and a half of guidance on the subject through Manual for Streets. Neither of these challenges should be something we shy away from tackling from a national level down to each case to deliver the benefits that a good public realm provides.

The pattern of our lives seems to be increasingly individualistic. However, the public realm is still a forum for people to come together, meet and share a common experience of a place. The decisions we make every step of the way, from where we develop down to the kerb detail, will impact how successful these spaces are and how positively they can contribute to our lives.

[1] https://www.pps.org/article/the-power-of-10

[2] https://www.pps.org/article/lighter-quicker-cheaper

[3] https://globaldesigningcities.org/update/piazze_aperte_report-en/

[4] https://twitter.com/fietsprofessor/status/1605946251286962177?lang=en-GB

Credits

Image 3: cities-today.com